Project 36721

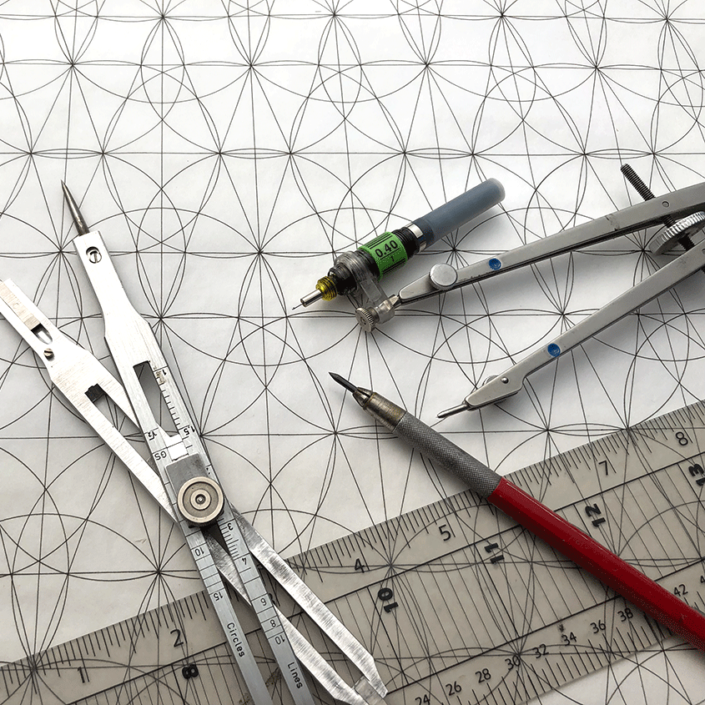

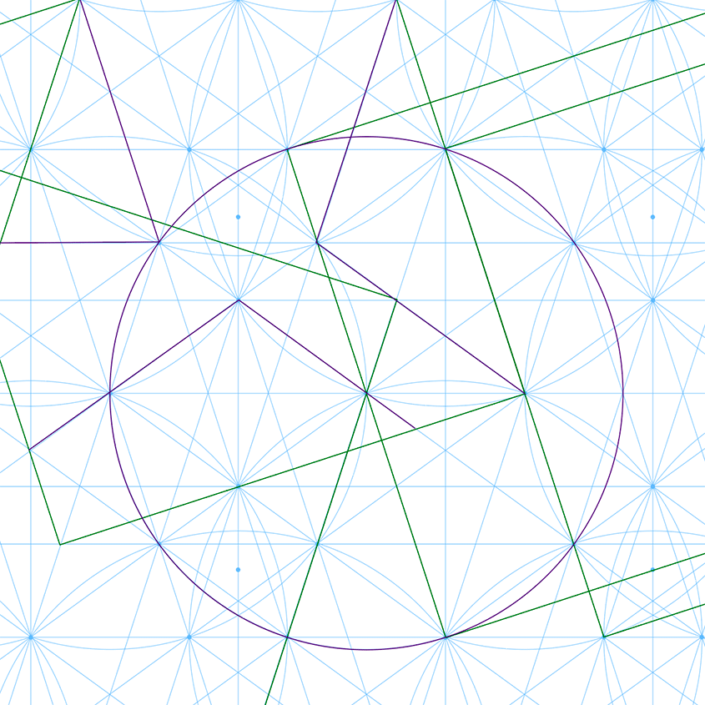

What began as a casual sketch evolved into a 42” x 120” drawing composed of intersecting arcs, circles, and straight lines suggesting periodic tilings of regular and irregular polygons. The drawing was made in black ink on 48”-wide drafting vellum bulldog-clipped to a 4’ x 8’ sheet of birch plywood, leaned up against a wall in an otherwise empty room. Armed with pencil, straightedge, proportional dividers and compass-mounted Rapidograph pen, I started my drawing at the bottom left-hand corner, working across the paper two rows at a time for three days in February, 1977. Years later, I would build a vector-based version of the grid with Adobe Illustrator.2

My work with this particular grid design during the mid ‘70s led to a series of drawings and paintings supported in part by a grant from the Connecticut Commission on the Arts. My installation entitled “No. 19” (96 x 96 x 96 in., acrylic on canvas and polyester) was included in the exhibition Connecticut Drawings, Painting and Sculpture 1978.

Much of my art and graphic design work of the past 40+ years is informed by the shapes, spatial relationships, patterns, and proportions of line segments expressed in this grid’s design.

The Project 3672 grid is similar to an isometric grid in that both provide for drawings showing multiple surfaces of three-dimensional objects without involving perspective. The three axes in isometric projections are formed by a vertical line with two horizontal lines intersecting at 30° angles. Axes remain parallel and never converge. No vanishing point, no horizon line. On the other hand, the Project 3672 grid has axes of 36° and 72° intersecting with its vertical axis, allowing for more complex projections and drawings than its isometric counterpart. Objects overlap in stacked layers. Sequences and patterns emerge. No beginning, no end.

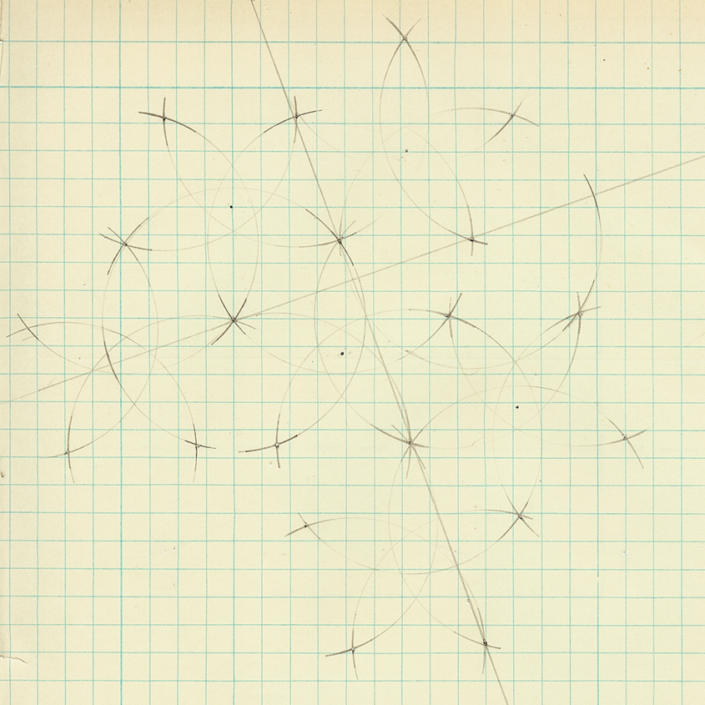

I started this project some 50 years ago simply out of curiosity, drawing circles connecting along a couple of straight lines in an old high school physics lab workbook. Since then, I’ve gathered a lot of information on various grid systems, tilings and tessellations including the work of 17th century mathematician Johannes Kepler, Oxford physicist Roger Penrose, and Albrecht Dürer’s hand-drawn pentagon tilings published in The Painter’s Manual in 1525. My sketchbooks and journals are full of notes, drawings and diagrams, renderings and plans for installations measured only in relative proportions. The work goes on and the grid is there, in the background.